Ready or Not, the A.I. Revolution is Here

When the historians of the future look back on the history of humanity, 2022 will likely be viewed as a watershed moment in artificial intelligence (A.I.). From the often sublime illustrations of DALL-E 2 to the unnervingly human-like writing of ChatGPT-3, society has been shocked and awed by the incredible advances made toward the A.I. of our science fiction fantasies (or nightmares?) Computer scientists have spent years developing the neural network infrastructure that powers these revolutionary tools, but only in the latter half of 2022 have these tools finally become available to the general public for the first time.

The reaction of the general public toward these new tools truly spans a broad spectrum: some are in awe of their capabilities and optimistic about their potential applications, while many others are at best skeptical of their true worth, and at worst, terrified by the potential ramifications of their widespread use. What I have found to be consistent across the spectrum, however, is a general ignorance of the workings of these tools, as well as a certain, lazy “belief of convenience” philosophy when it comes to forming opinions about A.I.

To call me anything remotely close to an expert on A.I. would be wrong, but I don’t think I’m ignorant when it comes to the subject. I can’t speak for those who are truly “plugged in,” as it were, to the tech world, but I certainly hadn’t realized just how good A.I. had gotten. If we had thought that there would be enough time in the future to discuss the role that A.I. should play in society, we were wrong. A.I. is here, and, as history has proved, resisting the onward march of technology is a fool’s errand. Regardless of your personal opinion on what the A.I. revolution bodes for the future, it will have an unimaginable impact on all of our lives.

Before discussing the societal implications of these new A.I. tools, it is imperative that we understand how these tools work, and perhaps more importantly, how they don’t work. What exactly is ChatGPT-3 doing, anyways, when it writes a short story about a constipated squirrel named Jarold in the style of Edgar Allan Poe?

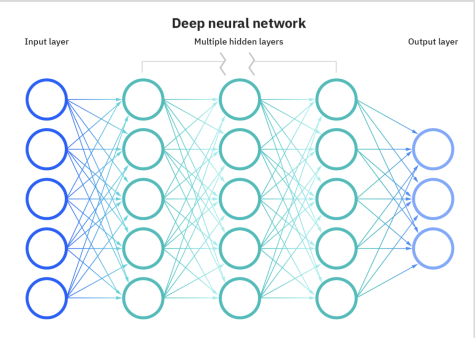

The A.I. revolution has largely stemmed from the development of artificial neural networks. Artificial neural networks are loosely modeled after how the brain works, with one or more layers of nodes (like the brain’s neurons) sandwiched between input and output layers, connected by countless (literally countless) connections (synapses). Similar to the brain, nodes receive and process signals, and based on the weight of the signal and the threshold of the given node, they decide whether to send the signal to the next node.

Using massive data sets made available only in the last few decades, neural networks can be trained, adjusting the weights and thresholds of their nodes to gradually increase their accuracy, until eventually, what is called a deep learning algorithm is produced. This is a simplified explanation: here’s a more in-depth explanation, if you are interested.

With the first two decades of the century seeing massive improvements in computing powers and the development of specialized computer chips, neural networks have become the most successful way to create deep learning algorithms. The success of the neural network approach has compounded upon itself, attracting billions in investment dollars from major technology firms, which has supercharged the development of the technology. In the last few years, companies have begun to unveil the product of their years of research and work, and the results have been mixed.

Scientists have been able to do some pretty incredible things using deep learning algorithms. Neuroscientists were able to map the roughly one hundred thousand neurons of a fly brain, once a nearly impossible achievement, and Google’s DeepMind used the AlphaFold algorithm to predict some two hundred million proteins, nearly every protein known to scientists. Some deep learning algorithms can detect diseases and identify cancers, often with greater accuracy than doctors, while other algorithms can model complicated weather and climate events. It would be wrong to discount the many positive applications of A.I. in society; science will benefit greatly from the widespread application of deep learning algorithms.

ChatGPT-3, the tool that has attracted the most attention in recent months, is a particular kind of neural network called a generative adversarial network. Generative A.I. models draw upon gigantic data sets to produce new, synthetic data based on the pattern of the original data. ChatGPT3, in the simplest of terms, is a model that predicts the next word in a sentence, based on a user prompt. When the model does that a couple of hundred times, the result is writing that very convincingly mimics human writing. Deep learning algorithms like ChatGPT-3 are, by their very nature, black boxes. Developers know what goes in and what comes out, but it is extremely difficult to know exactly what goes on inside and how or why ChatGPT-3 does what it does. However, one thing does seem quite clear: ChatGPT-3 doesn’t understand the meaning of the words it produces, at least not in the sense that a human understands their meaning.

Ezra Klein, a writer at the New York Times, paraphrasing the philosopher Harry Frankfurt, described the writing of ChatGPT-3 as, in the most philosophical sense, bullshit: “It is content that has no real relationship to the truth.” What is true and what is false has nothing to do with what content the model produces. ChatGPT-3 works by synthesizing and copying the writing in its datasets, and because it doesn’t discriminate as to whether the source material is accurate or not, it cannot help but often produce false information. To quote the guest on Klein’s podcast , the Ezra Klein Show, professor emeritus Gary Marcus, “These systems have no conception of truth… they’re all fundamentally bullshitting in the sense that they’re just saying stuff that other people have said and trying to maximize the probability of that. It’s just autocomplete, and autocomplete just gives you bullshit.”

Even when accuracy isn’t the goal, such as in the case of fictional stories or prose, ChatGPT-3’s writing isn’t especially inventive. Ian Bogost, a writer for The Atlantic, has written about the incredibly formulaic nature of the model’s writing, most often following the standard five-paragraph model that characterizes most grade-school writing. Play around with ChatGPT-3 a bit for yourself: as I did, you may find that it loves to write happy endings, regardless of the subject matter. Patterns pervade the way that it writes, but that shouldn’t be surprising; the very essence of generative A.I. tools like ChatGPT-3 is that they create synthetic content by following patterns.

That doesn’t mean that ChatGPT-3’s writing is useless. The model excels at copying essay formats, and after all, most of the writing humans do basically amounts to copying what has been written before. Indeed, most school assignments require that students closely follow a model format when constructing most of their writing. It’s not difficult to imagine a world where ChatGPT-3 replaces humans when it comes to the “grunt work” of writing.

But as discussed in Bogost’s piece in The Atlantic, the model often cannot attain the beauty and originality of prose that a human can harness; because the model is restricted by the content of its datasets (what has already been written), it often fails at writing creatively. Furthermore, because ChatGPT is so formulaic, models have already been developed to detect whether writing was synthetically created by ChatGPT3. One could conceivably imagine an arms race between chatbot models and chatbot detection models, with developers on both sides seeking an edge in the A.I.-created content world.

One of the most notable capabilities of ChatGPT3 is writing code. For years, researchers in natural language processing (NLP) have sought to make coding more accessible to the general public by allowing users to speak in natural language — the vernacular we use in our everyday lives — to program computers. Instead of requiring knowledge of the specific syntax and nuances of coding languages, NLP allows for someone relatively untrained in computer science to write programs and algorithms for whatever they might need. ChatGPT is an NLP, and it has proved to be a major step towards allowing everyday people, without computer science knowledge, to write code. If you ask ChatGPT3 to write a program in a given language to do a given task, all in your everyday vernacular, it will write you a program to do that task. That’s a pretty big deal.

Some have declared the end of the take-home essay assignment from schools. For a couple of reasons, I don’t think that we’ve reached that point yet. As mentioned previously, A.I. writing isn’t so good that it is impossible to identify it. If students begin using ChatGPT-3, and presumably the other models that arise to challenge it, to cheat on assignments, schools and teachers would likely begin to use detection software to catch the synthetic compositions. Furthermore, given the high operating cost of ChatGPT-3, it is unlikely that it will remain free for long. ChatGPT3 is only free because it is currently in beta testing; the developers want not only to spread the word about how good their technology has become but also to see all of the different ways that the model could go wrong. OpenAI will presumably want to start making money as soon as they can. This opens the door to potential inequities; wealthier students may have access to advanced A.I. tools like ChatGPT3, while poorer students are unable to afford such tools.

New York City public schools have already moved to ban ChatGPT, citing the potentially harmful effects on the learning of students, chiefly that students will rely too heavily on the tool and not develop essential critical thinking skills. They have a point: many writing assignments are less about the written product and more about exercising critical thinking to form an argument and craft a piece of writing. Speaking as a student, using ChatGPT-3 for your assignments is probably not very good for your education. Relying on ChatGPT-3 for factual information is also not a good idea; the model frequently produces incorrect statements. As stated before, ChatGPT-3 doesn’t have any conception of whether information is true or not; it is just trying to predict the next word in a sequence.

In addition to the risks of cheating, the vast potential for the nefarious use of ChatGPT-3 cannot be ignored. While there are safeguards in place to prevent someone from asking something like how to build a bomb, they can sometimes be circumvented through peculiar means, such as embedding the question in a request for the A.I. to write the script for a play.

In a further illustration of the potentially dangerous misuses of A.I, several months ago, Radiolab aired an episode about a particular algorithm designed to discover medicines for rare diseases. One of the creators, however, soon realized that by changing only a couple of parameters, they could instead predict the most powerful chemical weapons known to science. To a certain degree, the piece was alarmist. Predicting a chemical is one thing; creating and synthesizing a chemical is another matter entirely. But the episode illustrates an important point; although the creators of deep learning algorithms may have benevolent intentions, it is all too easy to conceive of evil applications for any technological tool. The analogy of a hammer as both a useful tool and a devastating weapon is especially apt in the case of generative A.I.

I don’t believe that OpenAI, the creator of ChatGPT-3, has any malicious intentions, but I also don’t think they realize the power that they’ve unleashed upon society. No one, not tech companies, not citizens, and least of all regulators, are prepared for the A.I. revolution. We can’t predict all of the different ways that A.I. will affect our society, but what we can predict indicates that the impact will be astounding.

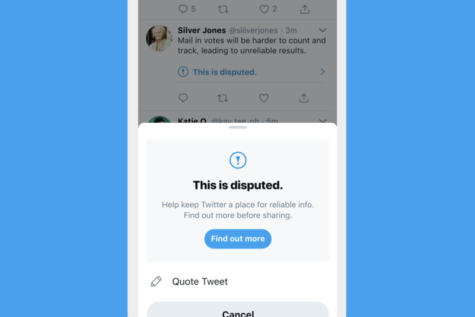

Just as there is a bot that can predict powerful chemical weapons, there is a bot that can write convincing misinformation with a very low marginal cost: it’s called ChatGPT-3. The potential consequences of allowing any individual actor to spread misinformation on a massive scale could be devastating. Deep learning algorithms could potentially heighten inequalities through data-driven biases, as well as intensify polarization through the spread of inflammatory rhetoric. To paraphrase Ezra Klein, the marginal cost of bullshit will be driven to practically zero.

As language processing models become more advanced — which they already have; although not yet released to the public, ChatGPT-4 is reportedly even more impressive than ChatGPT-3 — many jobs that were previously considered safe from technological encroachment may risk being automation. As has happened in the past, these technology-driven job turnovers have ripple effects throughout the economy and society at large. The question of who should own, control, and most importantly, profit from these deep learning algorithms is yet unresolved. Revolutions in the past have been focused on control of the “means of production”; and without regulation and a societal conversation about these technologies, we risk similar unrest. Who should be able to harness the incredible power of deep learning algorithms?

Human creativity has not been supplanted (yet), but we must carefully consider the impact of these revolutionary technologies. They are hammers, with the ability to cause both great societal benefits and harm, and on every level of society, we must decide how we want these technologies to impact our lives. Parents must consider how their children should interact with A.I. tools just as they consider how their children interact with social media and the internet. Schools should hold dialogues that include not only administrators, but also students, teachers, and parents about how deep learning algorithms should be implemented in schools. Governments must act decisively to stay ahead of bad actors and to prevent the formation of A.I. monopolies, as well as to incentivize applications of A.I. that are beneficial to society.

The genie may already be out of the bottle, but I don’t think that corporations should be making these decisions for us. While our government is flawed at best and an absolute trainwreck at worst, at least we have some say in the actions of our government; we have no direct say in the actions of a corporation. We must start having conversations about how to manage the powerful new capabilities that are entering our arsenals, and we need to have them now, or else we might not have a chance until it is already too late, and companies like OpenAI have already made the decision for us.