How do you live? With malice? With care? Intentionally? Absent-mindedly? Controlled by grief and bitterness or awash in joy and acceptance? What compels you to navigate life in such a way?

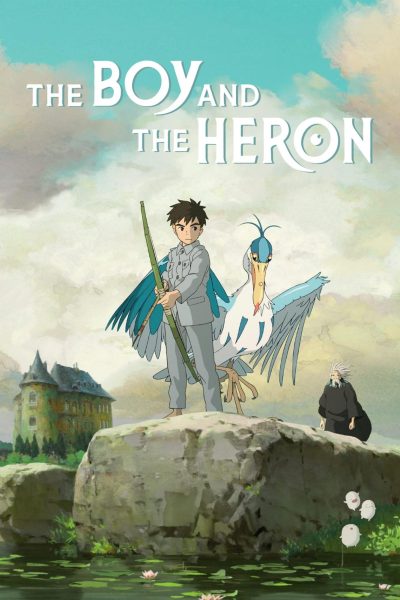

After a development cycle of about seven years, Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki’s “final” picture The Boy and the Heron has fully released in American theaters. How Do You Live? (the film’s original, translated title) emerged in Japan last summer with almost complete obscurity, as advertising included only an abstract poster and a few stills. That’s right, no trailer! No press tour! No fast food chain tie-in!

As if that stunt wasn’t groundbreaking enough, Heron also happens to be the most expensive Japanese film ever made, situating Miyazaki’s magnum opus (until he makes another one, at least) as a walking contradiction: it is both a tremendous pillar in filmmaking and a defiant snub of the commercialism and Hollywoodification that plagues the form itself.

But worry not. Due to the filmmaker intending the content to remain a mystery until one sees the film for themselves, this article will not be giving any plot details away. I went in knowing almost nothing other than the names of a few actors on the English dub, and I have no regrets.

For the record, Miyazaki’s dubs have been excellent lately, and Heron is no exception. Your local independent theater (shout out to my previous place of work, Squirrel Hill’s The Manor) will probably have both subs and dubs availability.

I recommend you do the same and honor the work’s behest. However, this film works best when viewed with the full context in which it was created. Sure, you can watch documentaries based on the Ghibli studio, research Shinto tradition, explore herons as symbols in Japanese folklore, but none of this is required to enjoy the work itself. Read on to learn a bit of context that helps you understand the weight of the art without knowing a single narrative beat.

First of all, how does anyone, let alone a legend like Miyazaki, follow the colossal farewell that was 2013’s The Wind Rises? The answer is they don’t, but this man doesn’t play by the rules. Whether formally or informally, he’s quit the profession no fewer than seven times throughout the course of his career.

Three years after his 2013 retirement, Miyazaki wrote this in his original project proposal for Heron: “There’s nothing more pathetic than telling the world you’ll retire because of your age, then making another comeback… Is it truly possible to accept how pathetic that is, and do it anyway? Doesn’t an elderly person deluding themself that they are still capable, despite their geriatric forgetfulness, prove that they’re past their best? You bet it does.”

Pathetic or not, I am grateful for this gift.

In anticipation of this achievement, I’ve been scraping the barrel of Ghibli films, painstakingly ranking them with each new viewing. And what a joyous task it’s been! As someone who already considered themselves a fan (heck, I’ve even rolled credits on the Ghibli RPG, Ni no Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch), I now feel like I have the required foundation for understanding the toppling reputation The Boy and the Heron is carrying on its shoulders.

The film is undeniably about Miyazaki himself; he has said the title is How Do You Live? because he sincerely doesn’t have an answer. The messaging has a clear throughline to him grappling with the acceptance that he won’t be around to tend to his family or studio forever, but also explores concepts of legacy, the pain of saying goodbye, and coming to terms with death–that last one being ironic considering the 82-year-old animation king can’t seem to step away from the throne after so many false retirements. Despite testimonials from those close to him stating that he’s genuinely tapping out this time, I’m almost convinced he will continue making movies until he physically can’t anymore, re-emerging from work-withdrawal like a perpetual phoenix.

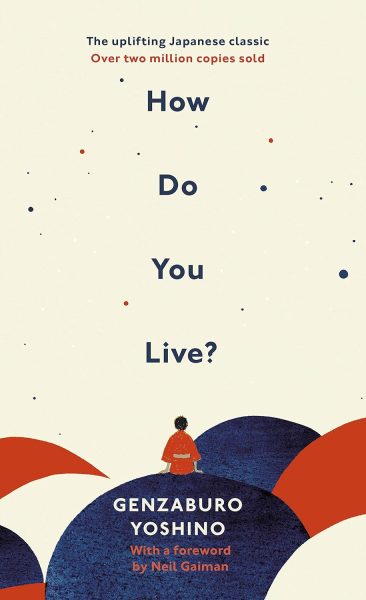

Loosely inspired by one of Miyazaki’s favorite books growing up, the once-banned 1937 instructive novel How Do You Live? by Genzaburō Yoshino, Miyazaki seeks to provide a heartfelt message to his grandson with this entry. While he will soon pass into the next world, he will still leave behind artistic reflections and “instructions” for his lineage; something to remember him by. Additionally, many are suspicious that this film also acts as a plea for his grandchildren to grab the torch and continue his animation legacy (after some reluctantly less-than-stellar entries from his son Goro Miyazaki). I’ll have you judge for yourself whether or not the film’s narrative supports that theory.

Loosely inspired by one of Miyazaki’s favorite books growing up, the once-banned 1937 instructive novel How Do You Live? by Genzaburō Yoshino, Miyazaki seeks to provide a heartfelt message to his grandson with this entry. While he will soon pass into the next world, he will still leave behind artistic reflections and “instructions” for his lineage; something to remember him by. Additionally, many are suspicious that this film also acts as a plea for his grandchildren to grab the torch and continue his animation legacy (after some reluctantly less-than-stellar entries from his son Goro Miyazaki). I’ll have you judge for yourself whether or not the film’s narrative supports that theory.

What I will say about the content of The Boy and the Heron is this: through his works, Miyazaki often speaks in what I’d call “dream language.” One might stumble out of his films much like they’d wake in the morning after a particularly vivid REM cycle: “What were those strange symbols? Those bizarre creatures? My parents were there, but only briefly, and they weren’t quite themselves at all times? What’s this thematic prodding getting at? What does it all mean?” Groggily, you continue with your day and remember these images until you pass out and see the next one.

Furthermore, Hayao Miyazaki’s stories are more about accepting change than they are about conquering a conflict. They don’t typically follow garden variety structures or cling to a Campbellian monomyth, or have all the played-out conventions we’ve come to expect from a Western feature film. I will attest that Hollywood has poisoned your mind if you bemoan the end of Spirited Away when Haku and Chihiro don’t end up together. The filmmaker respects our intelligence too much to give us anything less than what we’ve seen a million times over. This all being said, Heron can often find itself awash in abstractions, exploring concepts ranging from dreamy, poignant metaphors to what some might call a Jungian mess. While I found some moments of the new film incomprehensible at first, they weighed on me, the same way you might wonder what your fiery subconscious was trying to communicate to you in a dream. I haven’t been able to stop thinking about his story, its message, and the role it has in the animation world. While I recommend Heron to everybody, I understand it won’t be for everybody. Perhaps those who have yet to understand the weight of its history will miss out on the subtext. Perhaps those who have yet to grapple with grief will find the film clouded by conceptual metaphors. As someone who felt “ready” to experience this love letter to legacy, I can say I was blown away. Plus, when’s the last time you’ve seen an entirely hand-drawn feature film. Go see it on a big screen for the spectacle alone. Trust me.

And speaking of trust, I now present you with my definitive tier rankings of Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli’s films. Because these works are in a league of their own, a Miyazaki “B” should absolutely not be mistaken for a “B” overall–they’re largely S ranks with infinitesimal disparities between them. Note: these rankings are not subjective, but rather they are strictly objective, and nobody is entitled to their own opinion. Please keep that in mind as you judge. Mononoke and Kiki forever. Thank you.

Nana • Dec 17, 2023 at 3:47 pm

Finally someone agrees with Mononoke